Introduction

Control of postoperative pain is one of the most important factors in determining when a patient can be safely discharged from a surgical facility and has a major influence on the patient’s ability to resume their normal activities of daily living

3. Perioperative analgesia has traditionally been provided by opioid analgesics (Fig. 2).

However, extensive use of opioids is associated with a variety of perioperative side effects [e.g., ventilatory depression, drowsiness and sedation, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), pruritus, urinary retention, ileus, constipation] that can delay hospital discharge

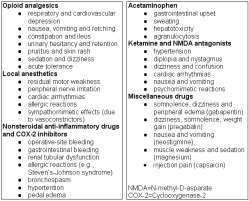

4. Intraoperative use of large bolus doses or continuous infusions of potent opioid analgesics may actually increase postoperative pain as a result of their rapid elimination and/or the development of acute tolerance 5. Partial opioid agonists (e.g., tramadol) are also associated with increased side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, ileus) and patient dissatisfaction compared to both opioid and non-opioid analgesics. Therefore, anesthesiologists and surgeons are increasingly turning to multi-modal (or balanced) analgesic techniques 6-7 for managing pain during the perioperative period to minimize the adverse effects of opioid analgesic medications.These multimodal analgesic techniques involve the use of smaller doses of opioids in combination with non-opioid analgesic drugs [e.g., local anesthetics, ketamine, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] are becoming increasingly popular approaches to preventing pain after surgery (Table 1) 4. This article will discuss recent evidence supporting the use of non-opioid analgesic drugs and techniques during the perioperative period for facilitating the recovery process, as well as review recent developments in the evolving field of non-opioid analgesia and review recent developments in the evolving field of non-opioid analgesia.

|

Table 1: Non-opioid Drugs Used for Minimizing Pain after Surgery† (adapted from White4) |

Local anesthetics· lidocaine, 0.5-2% SQ/IV · bupivacaine, 0.125-0.5% SQ · levobupivacaine, 0.125-0.5% SQ · ropivacaine, 0.25-0.75% SQ Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs· ketorolac, 15-30 mg PO/IM,/IV · diclofenac, 50-100 mg PO/IM/IV · ibuprofen, 300-800 mg PO · indomethacin, 25-50 mg PO/PR/IM · naproxen, 250-500 mg · celecoxib, 200-400 mg Miscellaneous analgesic compounds · acetaminophen, 0.5- · propacetamol, 0.5- · ketamine, 10-20 mg PO/IM/IV · dextromethorphan, 40-120 mg PO/IM/IV · clonidine, 0.15-0.3 mg PO/TC/ IM/IV · dexmedetomidine, 0.5-1 mg/kg, followed by 0.4-0.8 mg/kg/h IV · gabapentin, 600-1200 mg bid · pregabalin, 150-300 mg bid · magnesium, 30-50 mg/kg, followed by 7-15 mg/kg/h IV · neostigmine, 1-10 mg/kg EPI/IT · capsaicin, 0.5- |

Local Anesthetic Techniques

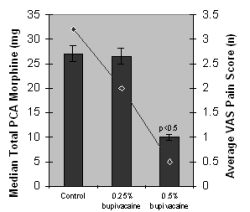

More effective pain relief in the early postoperative period, as a result of the residual sensory block produced by local anesthetics, facilitates recovery by enabling earlier ambulation and discharge home (i.e., “fast-track” recovery). In addition, use of local anesthetic-based techniques for preventing pain can decrease the incidence of PONV because of their opioid-sparing effects. However, these techniques are most effective for superficial procedures and the duration of analgesia lasts for only 6-8 hr after surgery.

Therefore, there has been increasing interest in using catheter systems (e.g., I-Flow’s On-Q

Fig 4

Peripheral nerve block techniques are simple, safe and highly effective approaches to providing perioperative analgesia. Use of long-acting local anesthetics for neural blockade techniques involving the upper (e.g., interscalene brachial plexus block) and lower (e.g., femoral-sciatic nerve block) extremities can facilitate an earlier discharge after major shoulder and knee reconstructive procedures, respectively.

Although ropivacaine is alleged to produce less toxicity and greater selectivity with respect to sensory and motor blockade than bupivacaine, these benefits have not been observed on a consistent basis.

Extending PNBs using disposable catheter systems improved recovery after both upper and lower extremity procedures

NSAIDs

Since parenteral preparations of NSAIDs (e.g., ketorolac, ketoprofen, diclofenac) have became available, these drugs have been more widely used in the management of acute perioperative pain. NSAIDs block the synthesis of prostaglandins by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) types I and II, thereby reducing production of mediators of the acute inflammatory response. By decreasing the inflammatory response to surgical trauma, NSAIDs have been alleged to reduce peripheral nociception. Studies also suggest that the central response to painful stimuli is modulated by NSAID-induced inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in the spinal cord.

|

Table 2: Recovery times after cardiac surgery in patients receiving saline (control), bupivacaine 0.25% (5 ml/h) or bupivacaine 0.5% (5 ml/h) at the median sternotomy site for 24-48 h after surgery (8) | |||

|

|

Control |

Bupivacaine 0.25% |

Bupivacaine 0.5% |

|

Extubation time (min) |

300 ± 118 |

396 ± 138 |

304 ± 140 |

|

First bowel sound (min) |

444 ± 302 |

231 ± 161† |

353 ± 258 |

|

Normal dietary intake (day) |

2 ± 0.7 |

1 ± 0.6† |

1 ± 0.4x |

|

Urinary catheter removal (day) |

2 ± 1 |

2 ± 1 |

1 ± 0.5x |

|

Sitting up in chair (day) |

1.2 ± 0.7 |

1 ± 0.6 |

1 |

|

Able to ambulate (day) |

2 ± 7 |

1 ± 0.6† |

1x |

|

First bowel movement (day) |

4.6 ± 1.4 |

4.3 ± 1.3 |

4 ± 1.5 |

|

ICU stay (hr) |

34 ± 12 |

40 ± 15 |

30 ± 10 |

|

Hospital stay (day) |

5.7 ± 2.1 |

5.0 ± 1.0 |

4.2 ± 0.8x |

Values are expressed as means ± SD

† Control group vs Bupivacaine 0.25%, p<0.05

‡ Bupivacaine 0.25% vs Bupivacaine 0.5%, p<0.05

ICU = Intensive Care Unit

Early reports suggested that parenteral NSAIDs possessed analgesic properties comparable to the traditional opioid analgesics without opioid-related side effects. In most studies, use of ketorolac has been associated with a less frequent incidence of PONV than the opioid analgesics. As a result, patients tolerate oral fluids and are fit for discharge earlier than those receiving only opioid analgesics during the perioperative period. Of interest, ketorolac (30 mg q 6 h) was superior to a dilute local anesthetic infusion (bupivacaine 0.125%) in supplementing epidural PCA hydromorphone in patients undergoing thoracotomy procedures

12.Furthermore, it has been found that the injection of ketorolac (30 mg) at the incision site in combination with local anesthesia may result in significantly less postoperative pain, a better quality of recovery, and earlier discharge compared to local anesthesia alone 13.

COX-2 Inhibitors

In an effort to minimize the potential for operative site bleeding complications, as well as gastrointestinal damage, associated with the classic nonselective NSAIDs ketorolac and diclofenac, the more highly selective COX-2 inhibitors became increasingly popular adjuvants for minimizing pain during the perioperative period. Early clinical studies demonstrated the benefits of using celecoxib (400 mg), rofecoxib (50 mg), and valdecoxib (40 mg) as preventative analgesics when administered for oral premedication. However, more recent clinical studies suggest a more sustained benefit can be achieved when these drugs are administered both before and after surgery 14-15. The recent withdrawal of rofecoxib and valdecoxib from the market because of their increased risk of cardiovascular side effects following prolonged use (>16 months), and wound complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, respectively, has led investigators to begin re-evaluating the role of COX-2 inhibitors in the perioperative period 16.

In addition to the growing controversy regarding the potential adverse cardiovascular events and wound infections with prolonged use of the COX-2 inhibitors in patients with cardiac disease 17, orthopedic surgeons have also expressed concerns regarding the potential negative influence of these compounds (as well as the traditional NSAIDs) on bone growth. Although COX-2 activity appears to play an important role in bone healing, a recent study by Reubens et al 18 found no effect of the COX-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) on bone healing after spinal fusion surgery when celecoxib was administered during the perioperative period.

Acetaminophen

Of the non-opioid analgesics, acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol) is perhaps the safest and most cost-effective non-opioid analgesic when it is administered in effective analgesic dosages (e.g., 30-50 mg/kg). Korpela et al 19 demonstrated that the opioid-sparing effect of rectal acetaminophen was dose-related up to 60 mg/kg. Although oral, parenteral and rectal acetaminophen produce opioid analgesic-paring effects in the postoperative period, concurrent use with a NSAID is superior to acetaminophen alone. The addition of acetaminophen, 1 g PO every 4 h, to PCA morphine improved the quality of pain relief and patient satisfaction after major orthopedic procedures 20.

An IV formulation of a prodrug of acetaminophen, propacetamol, has been administered to adults as an alternative to ketorolac in the perioperative period 21.

Propacetamol reduced PCA morphine consumption by 22-46% in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Given the adverse effects associated with both NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, use of acetaminophen may assume a greater role in postoperative pain management in the future.

NMDA Antagonists

Ketamine is a unique IV anesthetic with analgesic-like properties that has been used for both induction and maintenance of anesthesia, as well as an analgesic adjuvant during local anesthesia. As a result of its well known side effect profile (Table 3), ketamine fell into disfavor in the late 1980’s. However, adjunctive use of small doses of ketamine (0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV) appear to be associated with a opioidsparing effects and a less frequent incidence of adverse events and greater patient and physician acceptance 22.

Dextromethorphan, another NMDA receptor antagonist that inhibits wind-up and NMDA mediatednociceptive responses in dorsal horn neurons, has also been found to enhance opioid, local anesthetic and NSAID-induced analgesia.

Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists

The 2-adrenergic agonists, clonidine and dexmedetomidine, produce significant anesthetic and analgesic-sparing effects. Premedication with oral and transdermal clonidine decreased the PCAmorphine requirement by 50% after radical prostatectomy surgery 23. Clonidine also improved and prolonged central neuroaxis and peripheral nerve blocks, when administered as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen.

Dexmedetomidine is a pure α2-agonist that also reduces postoperative pain and the opioid analgesic requirement 24. Administration of dexmedetomidine, 1 μg /kg followed by 0.4 μg /kg/h, was also associated with a 66% reduction in PCA morphine use in the early postoperative period after major inpatient surgery.

Table 3: Potential side effects of opioid and non-opioid analgesic drugs used during the perioperative period (adapted from White4)

Future Developments in Non-Opioid Analgesia

Gabapentin (a structural analog of GABA) is an anticonvulsant that has proven useful in the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain and appears to be a useful adjuvant in the management of acute postoperative pain. Premedication with gabapentin (1.2 g po) reduced postoperative analgesic requirement significantly without increasing side effects 26. Pregabalin, a related compound, has also been reported to possess analgesic potential comparable to ibuprofen when used to prevent acute dental pain 27.

Additionally, both magnesium 28 and neostigmine 29 may prove to be useful non-opioid adjuvants for improving patient comfort in the postoperative period. In the future, long-acting local anesthetic formulations (e.g., liposomal and suspension solutions) and drugs which alter the sensory nerve endings (e.g., pregabalin, capsaicin) are likely to assume increased importance for minimizing postoperative pain. Despite its poor absorption, capsaicin is currently marketed for topical administration. New formulations of capsaicin (ALGRX 4975) for injection and a gel for wound instillation are being developed specifically for the prevention of postoperative pain. Capsaicin’s mechanism of action involves localized degradation of the C-fiber nerve endings due to its ability to bind to and activate the vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1) on the surface of the C-fibers. Therefore, ALGRX 4975 appears to be a highly specific pain therapy that may provide long-acting analgesia after a wide variety of painful surgical procedures (e.g., bunionectomy, arthroplasty, herniorrhaphy, hysterectomy).

Summary

As more extensive and painful operations (e.g., laparoscopic cholecystectomy, adrenalectomy, and nephrectomy procedures, as well as prostatectomy, laminectomy, shoulder and knee reconstructions, hysterectomy) are performed on an outpatient or short-stay basis, the use of multimodal perioperative analgesic regimens involving small doses of potent opioid analgesics in combination with non-opioid analgesic therapies (Table 4) will likely assume an increasingly important role in facilitating the recovery process and improving patient satisfaction 30. Pavlin et al. 31 recently confirmed the importance of postoperative pain on recovery after ambulatory surgery. Moderate-to-severe pain prolonged recovery room stay by 40-80 min. Use of local anesthetics and NSAIDs decreased pain scores and facilitated an earlier discharge home. Additional outcome studies are needed to validate the beneficial effect of these non-opioid therapeutic approaches with respect to important recovery variables (e.g., resumption of normal activities [e.g., dietary intake, bowel function], return to work). Although many factors other than pain per se must be controlled in order to minimize postoperative morbidity and facilitate the recovery process 32, pain remains a major concern of all patients undergoing elective surgical procedures 1.

Opioid analgesics continue to play an important role in the management of moderate-to-severe pain after surgical procedures. However, adjunctive use of non-opioid analgesics will likely assume a greater role as minimally-invasive (“key hole”) surgery continues to expand 2-4. In addition to the local anesthetics, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, acetaminophen, ketamine, dextromethorphan, alpha-2 agonists, gabapentin, adenosine, capsaicin, magnesium and neostigmine may all prove to be useful adjuncts in the management of postoperative pain in the future. Adjunctive use of low-dose droperidol and glucocorticoid steroids (e.g., dexamethasone) also appear to provide clinically-significant beneficial effects in the postoperative period. Use of analgesic drug combinations with differing mechanisms of action as part of amultimodal regimen will provide additive (or even synergistic) effects with respect to improving pain control, reducing the need for opioid analgesics, and facilitating the recovery process.

Safer, simpler, and less-costly analgesic drug delivery systems are needed to provide cost-effective pain relief in the post-discharge period as more major surgery is performed on an ambulatory (or short-stay) basis in the future.

In conclusion, the optimal non-opioid analgesic technique for postoperative pain management would not only reduce pain scores and enhance patient satisfaction, but also facilitate earlier mobilization and rehabilitation by reducing pain-related complications after surgery 30. Recent evidence suggests that this goal can be best achieved by using a combination of preemptive techniques involving both central and peripheral-acting analgesic drugs

|

Table 4: Recommendations for pain management during the perioperative period in outpatients undergoing major ambulatory surgery procedures |

|

I. Administer an NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen 800 mg, celecoxib 400 mg po) or gabapentin II. Use small doses of potent opioids (e.g., fentanyl 25-50 mg, or sufentanil 5-10 mg IV) for treatment of moderate-to-severe pain during and/or immediately after surgery III. Consider intraoperative use of ketorolac 30-60 mg IV and opioid-sparing drugs (e.g., a2-agonists, ketamine, b-blockers, and Ca-channel blockers) IV. Supplement every operation with long-acting anesthetic at all surgical sites V. Consider the use of continuous peripheral (perineural) nerve blocks for painful extremity procedures VI. Provide ongoing “preventative analgesia” in the postdischarge period using oral non-opioid analgesic techniques to minimize the need for opioid-containing oral analgesics |

References

1. Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Metha SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003; 97: 534-40

2. White PF. Ambulatory anesthesia advances into the new millennium. Anesth Analg 2000; 90: 1234-5.

3. Chung F, Ritchie E, Su J. Postoperative pain in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 1997; 85: 808-16.

4. White PF. The role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of pain after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2002; 94: 577-85.

5. Guignard B, Bossard AE, Coste C, et al. Acute opioid tolerance: intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology 2000; 93:409-17.

6. Eriksson H, Tenhunen A, Korttila K. Balanced analgesia improves recovery and outcome after outpatient tubal ligation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40:151-5.

7. Michaloliakou C, Chung F, Sharma S. Preoperative multimodal analgesia facilitates recovery after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 1996; 82:44-51.

8. White PF, Rawal S, Latham P, et al: Use of a continuous local anesthetic infusion for pain management after median sternotomy. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 918-23.

9. Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wang RD, Enneking FK. Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 959-65.

10. White PF, Issioui T, Skrivanek GD, et al. Use of a continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block for the management of pain after major podiatric surgery: does it improve quality of recovery? Anesth Analg 2003; 97: 1303-9.

11. Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wright TW, et al. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2003; 96:1089-95.

12. Singh H, Bossard RF, White PF, Yeatts RW. Effects of ketorolac versus bupivacaine coadministration during patient-controlled hydromorphone epidural analgesia after thoracotomy procedures. Anesth Analg 1997; 84: 564-9.

13. Coloma M, White PF, Huber PJ, et al. The effect of ketorolac on recovery after anorectal surgery: intravenous versus local administration. Anesth Analg 2000; 90:1107-10.

14. Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Tuman KJ, et al. Effects of perioperative administration of a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor on pain management and recovery of function after knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 2411-8.

15. Ma H, Tang J, White PF, et al. Perioperative Rofecoxib improves early recovery after outpatient herniorrhaphy. Anesth Analg 2004; 98:970-5.

16. White PF. Changing role of COX-2 inhibitors in the perioperative period: is paracoxib really the answer? Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 1306-8.

17. Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2005; 17: 1081-91.

18. Reuben SS, Ekman EF. The effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhbiition on analgesia and spinal fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 536-42.

19. Korpela R, Korvenoja P, Meretoja OA. Morphine-sparing effect of acetaminophen in pediatric day-case surgery.Anesthesiology 1999;91:442-7.

20. Schug SA, Sidebotham DA, McGuinnety M, et al. Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patientcontrolled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 1998; 87: 368-72.

21. Zhou TJ, Tang J, White PF. Propacetamol versus ketorolac for treatment of acute postoperative pain after total hip or knee replacement. Anesth Analg 2001; 92:1569-75.

22. Guignard B, Coste C, Costes H, et al. Supplementing desflurane-remifentanil anesthesia with small-dose ketamine reduces perioperative opioid analgesic requirements. Anesth Analg 2002; 95:103-8.

23. Segal IS, Jarvis DJ, Duncan SR, et al. Clinical efficacy of oral transdermal clonidine combinations during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology 1991; 74: 220 5.

24. Arain SR, Ruehlow RM, Uhrich TD, Ebert TJ. The efficacy of dexmedetomidine versus morphine for postoperative analgesia after major inpatient surgery. Anesth Analg 2004; 98:153-8.

25. Zárate E, Sá Ręgo MM, White PF, et al. Comparison of adenosine and remifentanil infusions as adjuvants to desflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 956-63.

26. Turan A, Karamanlioglu B, Memis D, et al. The analgesic effect of gabapentin after total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 2004; 98: 1370-3.

27. Hill CM, Balkenohl M, Thomas DW, et al. Pregabalin in patients with postoperative dental pain. Eur J Pain 2001; 5: 119-24.

28. Kara H, Sahin N, Ulusan V, Aydogdu T. Magnesium infusion reduces perioperative pain. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2002; 19: 52-6.

29. Kaya FN, Sahin S, Owen MD, Eisenach JC. Epidural neostigmine produces analgesia but also sedation in women after cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2004; 100: 381-5.

30. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002; 183: 630-41.

31. Pavlin DJ, Chen C, Penaloza DA, et al. Pain as a factor complicating recovery and discharge after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:1627-32.

32. Kehlet H, Dahl JB. Anaesthesia, surgery and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet 2003; 362: 1921-8.